It must have been around May 2021 when I first listened to Friends at the Table’s playthrough of Fall of Magic. Friends at the Table is a long-running "actual play" podcast, in which a group of friends plays through tabletop RPGs together to tell stories. Fall of Magic is one of those many tabletop RPGs.

The series totals to three episodes, something like 9 hours of audio, roughly the length of an average audiobook. Originally formatted as live episodes exclusive to Patreon backers, it was later repackaged into regular episodes in the main feed. At the top, host Austin Walker warns about the fuzziness of the overall story: the intervening months between recordings had blurred their memories of precisely what happened prior, and the whole thing takes on a fairytale-esque air because of this.

That trio of episodes is very dear to me. I don't revisit media very often, especially podcasts, but these episodes are a comfort I return to once a year or so. They’re a work of storytelling that never fails to bring me quiet smiles, sudden laughter, pleasant daydreams, goosebumps, tears.

A couple of months ago, I reached the end of my very own campaign of Fall of Magic, played across a span of months with a group of dear friends. It was exciting to finally play the game myself, years after hearing those episodes. The lavish physical copy had been collecting dust on my shelf for nearly as long. Sitting down to play, I couldn't shake a nervous feeling that my own play experience might not measure up.

Our game, it turned out, was fairly different from the one that the Friends at the Table played. We were different friends at a different table. More importantly, it's surprisingly easy to forget that play is a remarkably different experience than listening.

But I absolutely enjoyed my play experience. I loved the contemplative and charming character beats and the clever world-building maneuvers that my friends and I came up with. Meanwhile, it also helped me forge a deeper understanding of Fall of Magic as a game, and the ways that it shapes collaborative storytelling.

The Elaboration Imperative

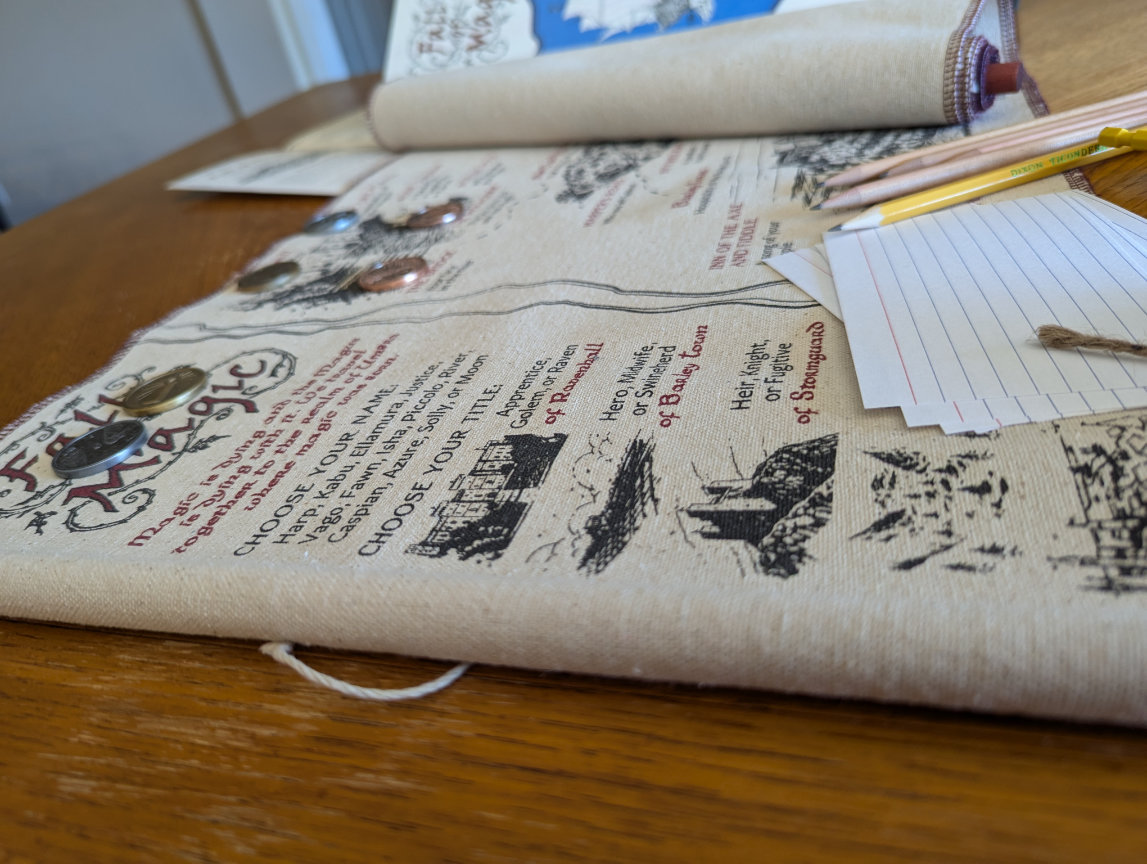

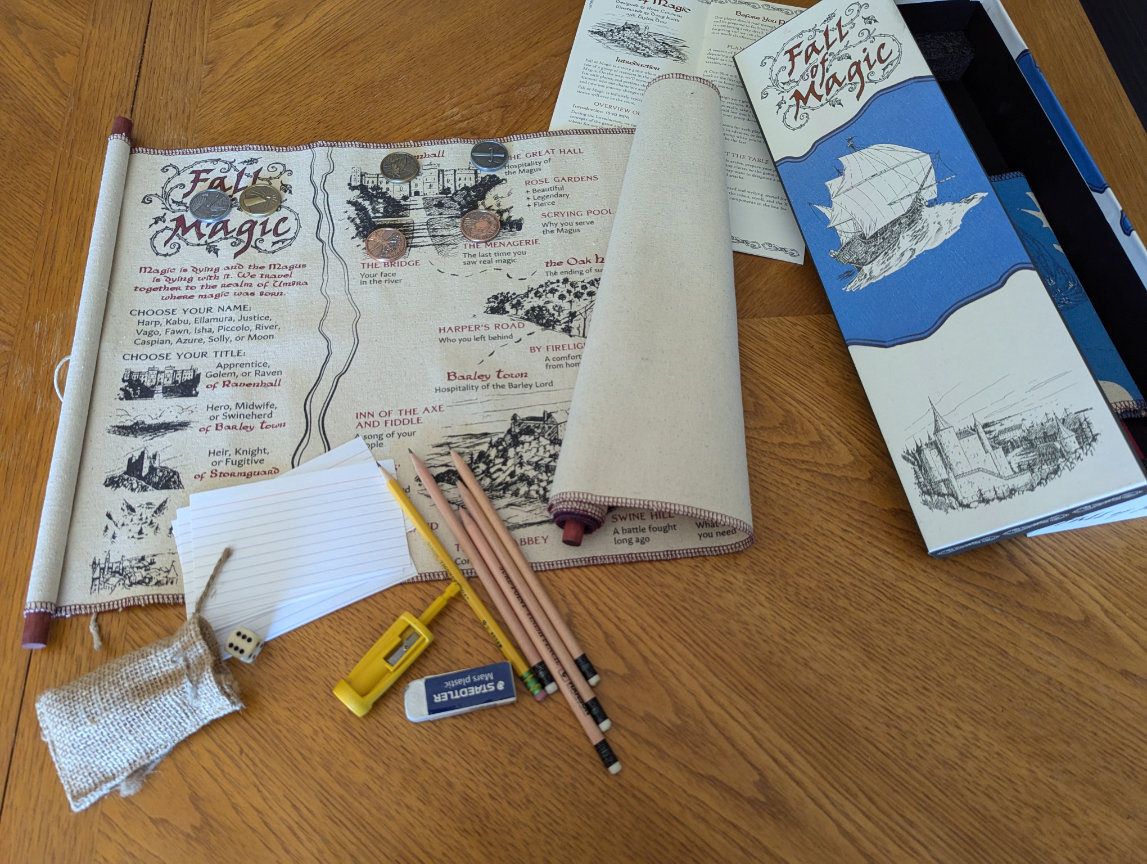

Fall of Magic is a storytelling game by Ross Cowman, with illustrations by Doug Keith and Taylor Dow. Its game text is laid out in a short booklet of vertically-folded pages and opens with a simple summary of its driving concept:

Magic is dying, and the Magus is dying with it. We travel together to the realm of Umbra where magic was born.

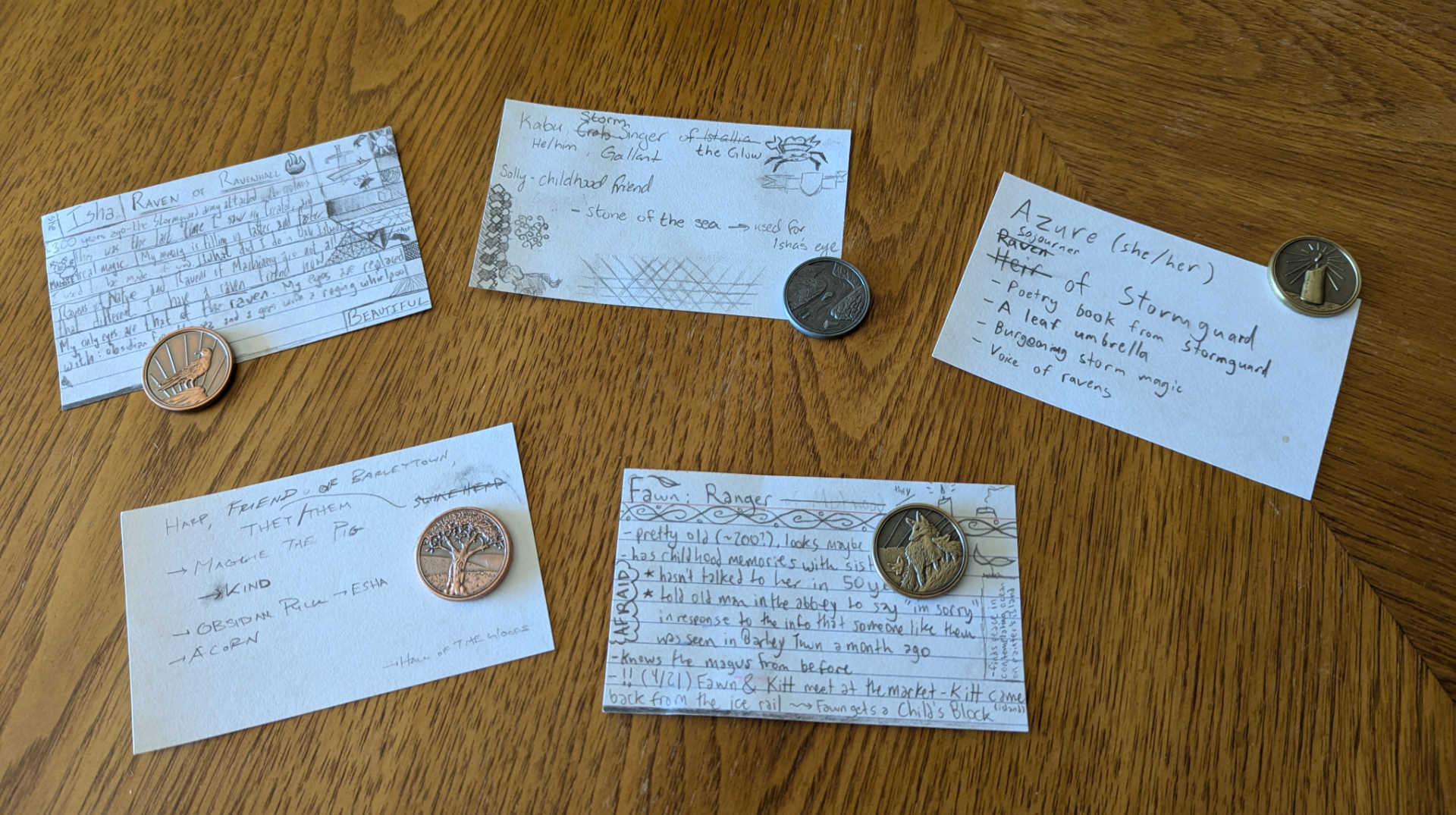

The game begins with creating very thinly-defined characters, no more than names and titles. Players then take turns exploring those characters, their quest, and the world they travel by answering a sequence of story prompts. Story prompts are simple questions answered by playing out scenes of your characters' experiences in the many places they visit during their journey.

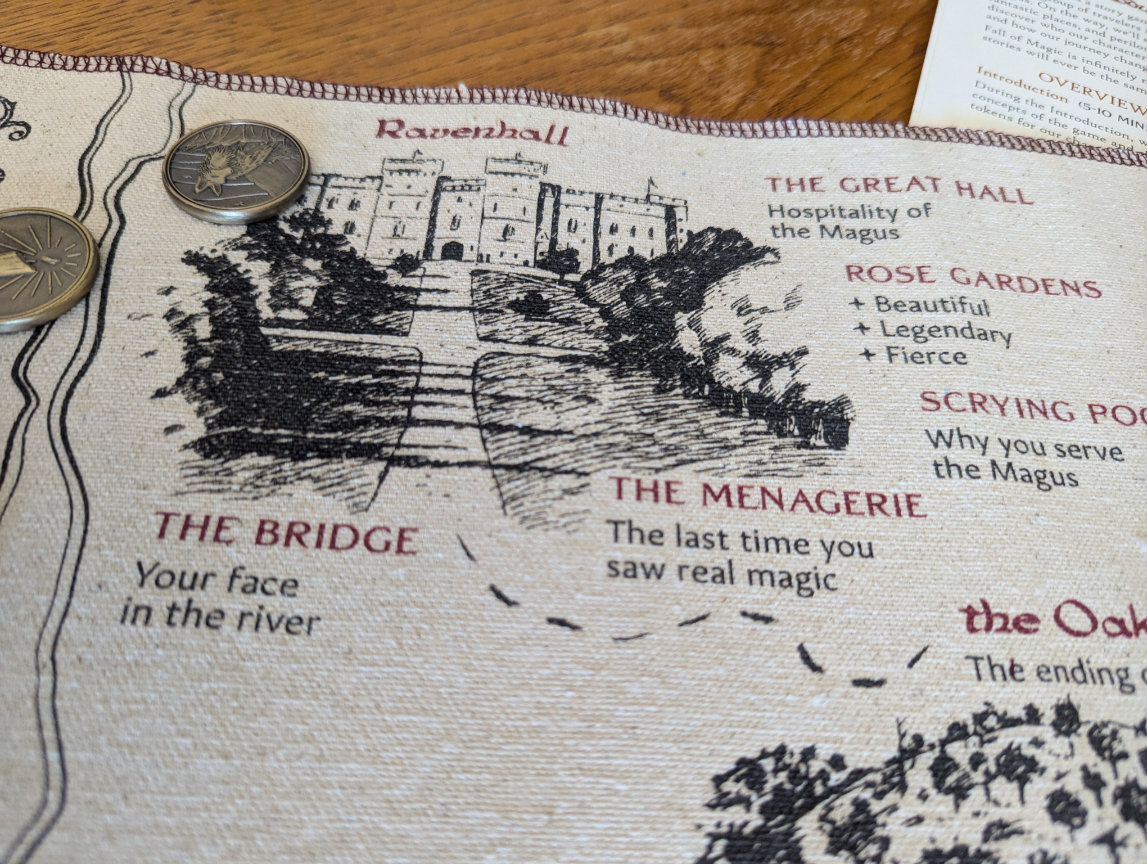

Playing the physical copy of the game involves incrementally unrolling a beautiful canvas scroll as your travelers make their way from place to place. The slow reveal of the scroll mirrors the characters' uncertainty about what might lie beyond the horizon. The Magus themself helps binds the group together: portraying the Magus is a shared responsibility, passed between players as they arrive at new locations and whenever they're needed in scenes.

The rules text is relatively brief. Aside from explaining the basic ideas (character creation, moving between locations, and a few light mechanical elements that occasionally crop up), it devotes a large portion of its words to framing the game and providing play examples and advice. The only narrative and world-building "content" of the game, as it were, can be found on the scroll itself.

Thus, the vast majority of the fiction in Fall of Magic is produced by elaboration: players read story prompts and location names, look at the lovely inked illustrations on the map, and then expand on these inspirations to form the details of their story.

To establish this pattern of elaboration, a seed is planted during character creation. Players choose a "title" for their character from a set of short lists; options include "Golem of Ravenhall", "Heir of Stormguard", or "Crab Singer of Istallia", for example. Sorry, a what of Istallia? Fall of Magic will not tell you what a Crab Singer is — this is where you come in. The rules text explains this with a simple, almost cheeky aside:

Someone may ask, “Is a Raven like the bird?” or “What is a Crab Singer?” To this we reply, “It means what you want it to mean.”

This maneuver is what I'll call an elaboration imperative. It's the fulcrum of Fall of Magic's design: little flourishes of phraseology that are insufficient on their own, but expansive in their implication. Each instance is incomplete in such a way as to be tantalizing and necessary to build upon. Most of the prompt and location language is less obtuse than "Crab Singer", but I like the example because of the immediacy of its appearance during character creation. It sets the stage for the elaboration imperatives that players will contend with frequently as the game progresses. From here on out, whenever players are presented with these evocative phrases, they will be tasked with exploding them into description and specificity during play.

Below, you can listen to the eponymous Friends taking the assignment very seriously (at least, for a couple of minutes):

The elaboration imperative largely serves as the engine for the rest of the storytelling, fueled by the drawings and prompts on the scroll. Despite the sparse text, players draw inspiration from the illustrations on the map and the affective aspects of unrolling the scroll and moving tokens across it. A cycle of moving, discovering, and expounding.

Crucially, the vast majority of Fall of Magic's prompts and locations are composed of simple English words, often concatenations and nearly always capitalized for dramatic effect. The deluge of proper nouns brings a sense of place and specificity, while the absence of explanation passes the buck to the players gathered around the table. Thanks to the plain English components, players have all the pieces they need to construct explanations both intuitively and creatively, as the podcast clip above demonstrates.

A Collaborative Story Game

While elaboration imperatives help initiate scenes in Fall of Magic, the rest depends on interplay between the player characters. The "How to Play" section provides a great deal of simple tools for telling stories in different ways, including asking questions of your fellow players, describing the scene conversationally, and supporting one another by filling the roles of side characters or environmental elements.

As mentioned before, players also share responsibility for portraying the Magus themself, who guides the travelers towards their destination. Thinking through the character of the Magus together is an early act of cooperation within the story. It tasks players with building a character who is distinctive enough to match the importance of their role, but characterized broadly enough that anyone can portray them. These cues led our table to a Magus who had the body of a human but the head of various animals; which head they “wore” would change from scene to scene to fit their mood and situation. "What animal head do they have in this scene?" became a recurring question for whenever the Magus appeared. Choosing an animal head became a tool for implying a tone for the scene (and sometimes unnerving our player characters).

Our characters all had different shapes to their personal story arcs, but moments of interplay between each other's ideas drove the broader story. More so than other scene-driven games I've played, Fall of Magic was frequently dependent upon multiple players contributing major world-building and character details to the same scenes, and it relied upon us remembering and teeing up one another's themes.

This push and pull created an interesting complexity to the act of collaboration. In addition to portraying characters, our scenes also needed to define terms or answer questions. We didn't always find formal ways of designating someone to collapse those narrative possibilities into truths within our fiction. Some of our clumsiest moments came from awkwardly hot-potato-ing this responsibility around to avoid stepping on toes or to give ourselves room to think and respond instead of invent.

As a group, we certainly had occasions where I felt that we stumbled, got in each others' ways, or failed to follow through. But we did get better at telling these stories together over the course of play, and part of it comes from beginning to apprehend the complexity of the world-building-as-you-go nature of the game. It soon became clear just how much fiction we were building collectively, compared to a game with a more concrete setting.

Making a Scene

These two mechanical pieces form the beating heart of Fall of Magic: the elaboration imperatives help establish the scene, and the collaborative interplay unravels it towards a conclusion. Aside from occasional story prompts that invoke a dice roll to determine their resolution, the world is unfolded almost entirely by the extrapolative work of the players.

This gets at the last major component of my experience with Fall of Magic. One might notice that "elaborate" and "collaborate" both derive from a Latin root that undergirds the word "labor". In other words, both elaboration and collaboration are forms of work, effort that we expend to turn the sparse words on the page into a compelling scene from our story. I use "work" to describe "effort" in an abstract sense; I'm not suggesting that it's compulsory or un-fun, or mutually exclusive with "play". Rather, this framing draws attention to the amount of active involvement that loosely-defined scene play demands, and the way it can be both intimidating and exhausting, especially for folks who engage with it as a hobby rather than a practiced craft.

All of this serves to explain why, after every session of Fall of Magic, I found myself feeling incredibly drained. Even with practice and with increasing familiarity with each other's goals and the game itself, the post-session exhaustion did not relent. It could almost certainly be mitigated by more thoughtful practices at the table: breaks, check-ins, shorter sessions. We had already discarded the standard turn order, instead taking turns as ideas came to us until we'd all gone once at each location. But the fact remained that this wore me out more than most other RPGs I've played (and I have the sense that my friends felt similarly).

Fall of Magic's lightness of rules is complemented by a heavier lift for the players themselves. Creating a good scene together involves following your fellow players' cues carefully, finding ways to give and take direction, sometimes explicitly and sometimes via implication alone. Simply put, it takes work; that's why playing scenes in story games can be so exhausting but also so gratifying. Fall of Magic winds up being "a lot of work" to play because it layers the basic challenges of scenecraft atop additional elaborative tasks. Getting in your character's head isn't enough. You may have to first figure out who or what "the Gilded One" is, or pause to determine what it means when a die result prompts you with "Heart of the Forest".

This perspective was missing from my understanding of Fall of Magic when I first started playing it. One reason that the game was so enticing was that it seemed to beget so much interesting fiction from such terse prompts. These tiny evocative phrases and inked drawings unravel into a big tapestry of storytelling, a journey whose scale is truly felt. But that doesn't simply happen; it's produced by the players at the table building upon those prompts. Fall of Magic does not make a lot from a little: it gives players the tools and inclinations to do this work themselves.

Beyond the Journey

Coming off of our final session of Fall of Magic, I was really high on the game. It felt like a truly grand journey, a complete adventure full of memorable moments. I wrote down a bunch of notes in anticipation of writing a blog post, and then... put them down. My musings seemed too effusive, insufficiently considered. Obviously there's nothing wrong with enjoying a game and writing about that experience. But I felt I hadn't fully processed it, and I had a nagging feeling that I needed some distance and perspective.

Coming back now, I'm thinking a lot more carefully about the design decisions that make Fall of Magic tick. I still feel very positively about the game! I also have a better understanding of how it functions and why it made me feel the way it did: fulfilled, but often exhausted.

Contending with this exhaustion was a big part of reaching that understanding. I've played other story games that made similar demands of their players, but rarely did they feel so intense and draining, and the difference seems to go beyond things like subject matter. Taking a step back let me consider that the usual challenges of scenecraft were layered on top of additional elaboration steps that simply increased the overall cognitive demand for explanation and invention. The true density and efficiency of Fall of Magic's great big scroll was not apparent until I realized this.

Ultimately, I now have an even greater appreciation of the sheer creative craft that goes into something like the Friends at the Table series that first introduced the game to me. I highly recommend those episodes to anyone interested. Not only do they tell a wonderful story, they also showcase how Fall of Magic's wistful fantasy writing and illustrations help to produce that story.

And while I also greatly recommend playing Fall of Magic yourself (the scroll is great, but the digital edition will do just fine), I also offer a word of caution: it's a lot more work than listening to a podcast.